by Seamus Cullen

In all the accounts of Bloody Sunday, little mention is made of the referee on that fateful day. Who was he and why was he appointed to such a significant role?

He was Mick Sammon – a 1919 All-Ireland medal winner with Kildare; and a volunteer who served time in three prisons for republican activity in 1918.

Little is known of his early footballing activities while working in Dublin apart from an involvement as a player with Hibernian Knights and Kickhams. In addition, he was a very well-known athlete, specialising in the 100-yard and 220-yard sprints.

It was following his move to Kilcullen that he blossomed as a Gaelic footballer. The Kilcullen club, known by the nickname ‘The Rags’, had moved up the ranks from junior to senior in 1914 and by the 1917 championship season Mick was captain with his team rivalling the leading senior teams in the county. He led the club to the 1917 county final which was played in January 1918. Their opponents Kilcock virtually consisted of a county team as it included many well-established county players from across the northern section of the county and emerged victorious.

At the beginning of the 1918 championship, Mick was selected on the county team joining four of the Kilcock players that he had played against in the county final, as well as Larry ‘Hussey’ Cribbin from his native village of Clane, and Larry Stanley who was emerging as one of the leading footballers in the game. This team was to bring All-Ireland success to Kildare the following year, 1919. In addition to partnering Larry Stanley at midfield, he was also the free taker. His reputation as a free taker is best described in a report from the Kildare Observer which stated ‘Sammon is the best man in Ireland to take frees … he leaves it easy for the forwards to score’.

The strongest team Kildare faced in the successful championship run was undoubtably Dublin whom they met in the Leinster final. Kildare emerged as victors by the lowest of margins, one point in a low-scoring game in which Kildare gained four scores. Mick had a part in three of the scores. He scored two points from frees and another of his frees found Jim O’Connor who scored the only goal. In the All-Ireland final, on 28 September 1919, with outstanding play by Larry Stanley, Kildare defeated Galway on a score of 2-5 to 0-1. Mick’s free-taking devastated the opposition and he not only got on the scoreboard but contributed to the two goals scored by Frank ‘Joyce’ Conlon and Jim O’Connor.

The War of Independence, which began in January 1919, increased with intensity during 1920 particularly following the death of Terence McSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork, in Brixton prison on 25 October. During this period, GAA inter-county challenge games were held to provide funds for the families affected by the ongoing national struggle and Mick was always ready and willing to offer his services both as a footballer and as a referee.

Throughout 1920 a munitions strike seriously hampered the British war effort. It began when workers refused to operate troop-trains, and this resulted in widescale hardship due to the dismissal of railway staff. A football match in aid of the Munition Workers Strike Fund was organised for Croke Park on 10 October 1920. The teams taking part were Kildare, the last team to win a senior All-Ireland, and Dublin, the team who had recently defeated Kildare in the Leinster final. An understrength Kildare team participated which included Mick Sammon who was only one of five players from the 1919 championship winning team to turn up. Not surprisingly, a near full-strength Dublin team won the game.[1]

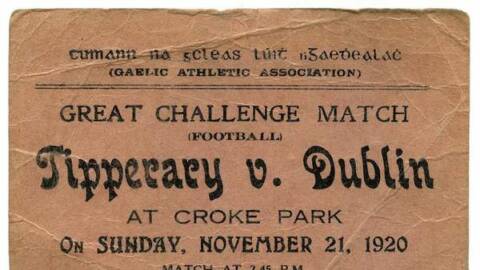

The following month, on 21 November, Mick was back again in Croke Park, on this occasion as referee for the Tipperary v Dublin challenge match. His expertise was not only confined to his playing abilities, but he also had shown certain capabilities as a referee. The proceeds on this occasion were in aid of the Republican Prisoners Dependents Fund, a cause that was of deep interest to Mick, a former political prisoner.

The Croke Park game began at 3.15pm, when Mick threw in the ball. Ten minutes into the game with no score from either side, the game was interrupted by the arrival of the RIC, Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans on the pitch. The subsequent firing by the Crown Forces resulted in the deaths of 14 people including the Tipperary player, Michael Hogan. Mick Sammon had been talking to Hogan moments before the shooting started and managed to crawl his way to the side-line when the firing commenced.

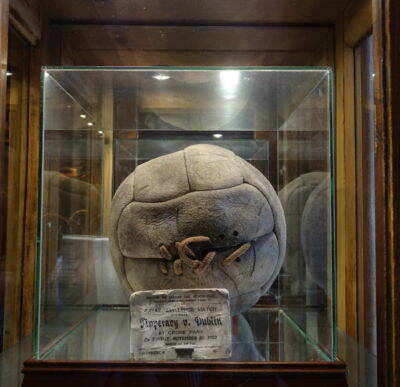

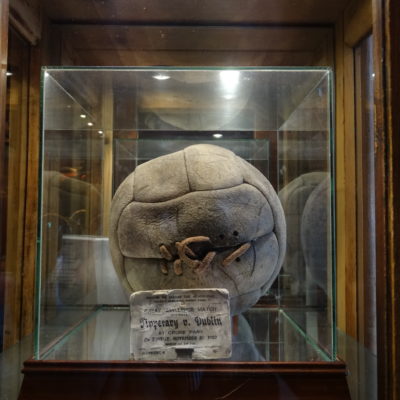

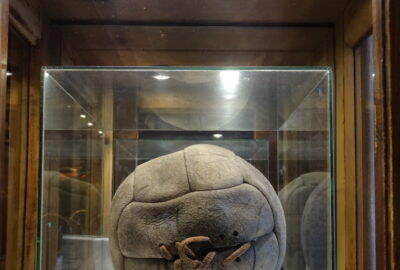

One year later, during the Truce, the challenge match between Tipperary and Dublin was replayed with Mick Sammon once again the referee. Out of respect to the memory of Michael Hogan the players wore crepe armbands. The game was officially started by Dan Breen, the legendary Tipperary freedom fighter, and the football used was presented by Mick Sammon.

During the period from 1919 to 1921, Mick was at the peak of his sporting career. He was recognised as one of the most accurate free takers in the game, in the top class of inter-county midfielders, nationally recognised as one of the best-known referees and he even found time to compete in athletics.

In early November 1920, Mick, in partnership with Paddy Moore, acquired the leasehold of a public house at 73 Fleet Street, Dublin, which was known as The Feathers (later named the Pearl Bar). Although this necessitated moving from Clane to Dublin he continued initially to play his football with Kildare. However, his work and interests in other activities resulted in football becoming less important. His interest in dogs and coursing increased.

Mick served on the Tailteann Games Committee which laid the groundwork for the restoration of the ancient Tailteann Games. When the National Athletic and Cycling Association of Ireland was formed, he served as treasurer to the Dublin Branch and was for many years a track judge at all the big meetings. He also served on a sub-committee appointed at the All-Ireland GAA Congress to consider a scheme for the formation of a new Irish Athletic Governing Body.

While not engaging directly in politics after 1918, Mick made his views known regarding politics and sport. He favoured the removal of the GAA ban on foreign games and publicly made his views known on the issue in an article in 1926 entitled, ‘politics that hamper sport’.

Throughout the 1920s, Mick continued to referee football matches. He took charge of the 1923 All-Ireland Junior final (Tipperary 2-6, Carlow 1-1) which was played in November 1924. The following year, on 26 April 1925, he refereed the 1924 All-Ireland Junior semi-final which was played prior to the 1924 senior final (Kerry 0-4, Dublin 0-3).

In 1938, Mick came out of retirement to referee a veterans’ charity football match, between Clondalkin Round Towers and Lucan Sarsfields, which was in aid of the Palmerstown Church fund.

Mick Sammon’s early life

He was born in Loughbollard, Clane on Tuesday 7 February 1893 to Thomas Sammon and Bridget Carty. He was named after his maternal grandfather Mick Carty from Baltracey. The Sammon (Salmon) family originated in Straffan and were from a rebel background. Mick’s ancestor was among several Sammon brothers who were arrested and imprisoned in July 1803 on suspicion of making pikes in Robert Emmet’s Thomas Street depot.

In the late 1850s, Mick’s grandfather, Maurice, relocated to Loughbollard, Clane. By the late-19th century, Clane was a centre of importance in the revival of cultural nationalism where one of the first GAA clubs in County Kildare emerged. Maurice Sammon was enthusiastically involved serving as Secretary of Clane GAA Club in 1891. That year the local Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) suspected that he was also a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). In 1898, when Mick Sammon was five years old, the centenary of the 1798 Rebellion was celebrated throughout Kildare. Both his grandfather, Maurice, and his father, Thomas, were members of the Clane committee that commemorated the event locally.

Mick served his time as an apprentice barman in the Cosgrave-Burke public house, 174 James’s Street, Dublin, close to St James’s Hospital.[1] The Cosgrave-Burke family were strongly nationalist with County Kildare connections. Bridget Cosgrave-Burke, owner of the public house was from Landenstown close to Prosperous. The proprietors were Frank Burke, Bridget’s second husband, and her eldest son, Willie Cosgrave, better known as W.T. Cosgrave, later President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, 1922-32, who, would, most likely, have further influenced Mick Sammon’s already strong political leanings.

Having served his time as a barman in James’s Street and later working in Essex Street, Mick moved back to County Kildare obtaining a position in Kilcullen, the Kildare town where he was to make an impact – initially in sport but mainly as a political activist.

Involvement in the national struggle, 1917-18

The period following Easter Week 1916 saw a transformation in politics with political support shifting from the Nationalist, Irish Parliamentary Party to the Sinn Féin movement which adopted republican principals. In mid-1917 a branch of Sinn Féin was established in Kilcullen and Mick Sammon was elected Vice-chairman. The following December a South Kildare executive of Sinn Féin was established with Éamon Ó Modhráin as President. Mick Sammon was one of the two delegates attending from Kilcullen and was elected a joint Treasurer on the executive. The Volunteer movement also extended throughout every parish in the county and Mick was elected an officer of the local volunteer branch in Kilcullen.

Mick Sammon’s most important activity in the national struggle at this period was his involvement in the general protest against the permit system imposed by the Dublin Castle authorities. During the Conscription Crisis in early 1918 new laws were enacted which made it illegal to hold a meeting or sporting event without having obtained a permit from the RIC. The GAA opposed the measure and successfully outmanoeuvred the authorities on the day known as Gaelic Sunday, 4 August 1918. On that day every club in the country held sporting events without seeking the required permit which rendered it impossible for the Castle authorities to arrest or charge a large section of the population.

Sinn Féin now decided to follow the example of the GAA by holding meetings without permits all over the country on Lady Day, Thursday 15 August, at which a statement supplied by headquarters comprising the party’s manifesto should be read out by a prominent local activist at an after-Mass meeting. Three meetings in County Kildare were held at Kilcock, Kilcullen and Athy. Activists that read the statement were Michael Stapleton at Kilcock, Mick Sammon at Kilcullen and at Athy a local teacher James J. [JJ] O’Byrne. Mick Sammon was the best known of the three because of his membership of the county football team.

Two days later, all three men that addressed the meetings in County Kildare were arrested as well as others in different parts of the country.

The three Kildare men were held in custody without trial in the Curragh Camp prison until 20 September when they were court marshalled in Maryborough Barracks on two charges: first, of taking part in a meeting without a permit and the second, making statements likely to cause disaffection. All three adhered to Sinn Féin-Volunteer policy by not giving recognition to the court. According to a correspondent, Mick Sammon when asked to plead, replied, ‘As an Irishman, I refuse to recognise the court’. Two of the men, O’Byrne and Stapleton, were convicted on both charges and sentenced to prison for one year with hard labour. Mick who made no defence was convicted of the first charge only. This may have been because when he was beginning his address at the banned meeting the Sergeant was called back to the barracks to receive a dispatch from the District Inspector and did not fully record his speech. Mick was given a sentence of one month’s imprisonment to run from 20 September.[2]

He served most of the sentence in Mountjoy Jail, Dublin before being transferred on 10 October to prison in Belfast. His prison record from Mountjoy provides considerable personal information including his prison number, 813, his height, five foot nine and three-quarter inches, brown hair, blue eyes, fresh completion and his weight, 175 lbs. His occupation was given as a shop assistant and his next of kin was his brother Thomas Sammon from Clane. Although the Lady Day meetings were not as successful as Gaelic Sunday as they led to the imprisonment of activists, nonetheless the arrests continued to enhance the status and popularity of Sinn Féin in the run-up to the General Election of 1918. Having spent a total of two months in prison, Mick was released in late October. At this point he relocated from Kilcullen to his native Clane taking up residence in the family home in Loughbollard.

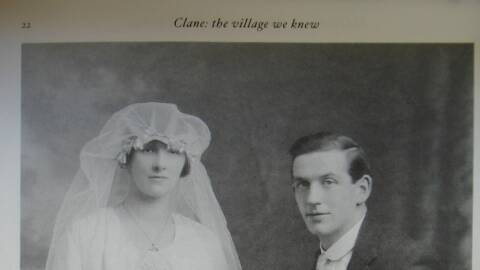

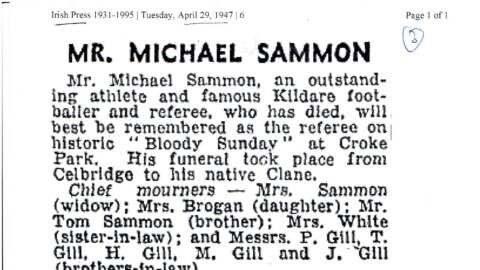

On Monday 26 June 1922, Mick married Elizabeth Gill, from Butterstream in his native Clane. The couple had two daughters, Betty and Maeve. He subsequently sold his interest in The Feathers Bar in Fleet Street and purchased The Railway Hotel (now The Abbey Lodge Pub) in Celbridge settling down to a life as a publican in his adopted town. He died on Thursday 24 April 1947 in Peamount Sanatorium after a short illness at a relatively young age of 54 and is interred in the Franciscan Friary Cemetery, Sallins Road, Clane.

Mick Sammon, nationalist, political prisoner, All-Ireland medal-winner and Bloody Sunday referee deserves to be remembered for his enormous contribution to Irish life.

[1] Irish Press, 21 Dec. 1966.

By christinemurray06 Sat 21st Nov